When “Selective Eating” Is Actually a Brain-Based Sensory Response

If mealtimes in your home feel stressful, you’re not alone.

Many parents tell me the same story: their child eats only a handful of foods, reacts strongly to new textures, gags or cries at the table, or refuses meals altogether. What starts as concern slowly turns into a daily worry.

Is my child eating enough? Am I doing something wrong?

Let me reassure you early on: not all selective eating is behavioral. Sometimes, it’s the brain responding to sensory overload.

Picky Eating Vs Sensory Food Aversion

Most children experience a picky eating phase, typically between the ages of 2 and 5. This is usually a normal developmental stage. These children may refuse foods today and accept them later. They might protest, but they can usually tolerate change over time.

Sensory-based food aversion looks very different.

Here, the reaction is intense, consistent, and distressing. The child isn’t choosing not to eat, but their nervous system is reacting as if the food is unsafe. These patterns don’t come and go easily, and they often cause anxiety around meals.

The key difference is patterns over phases.

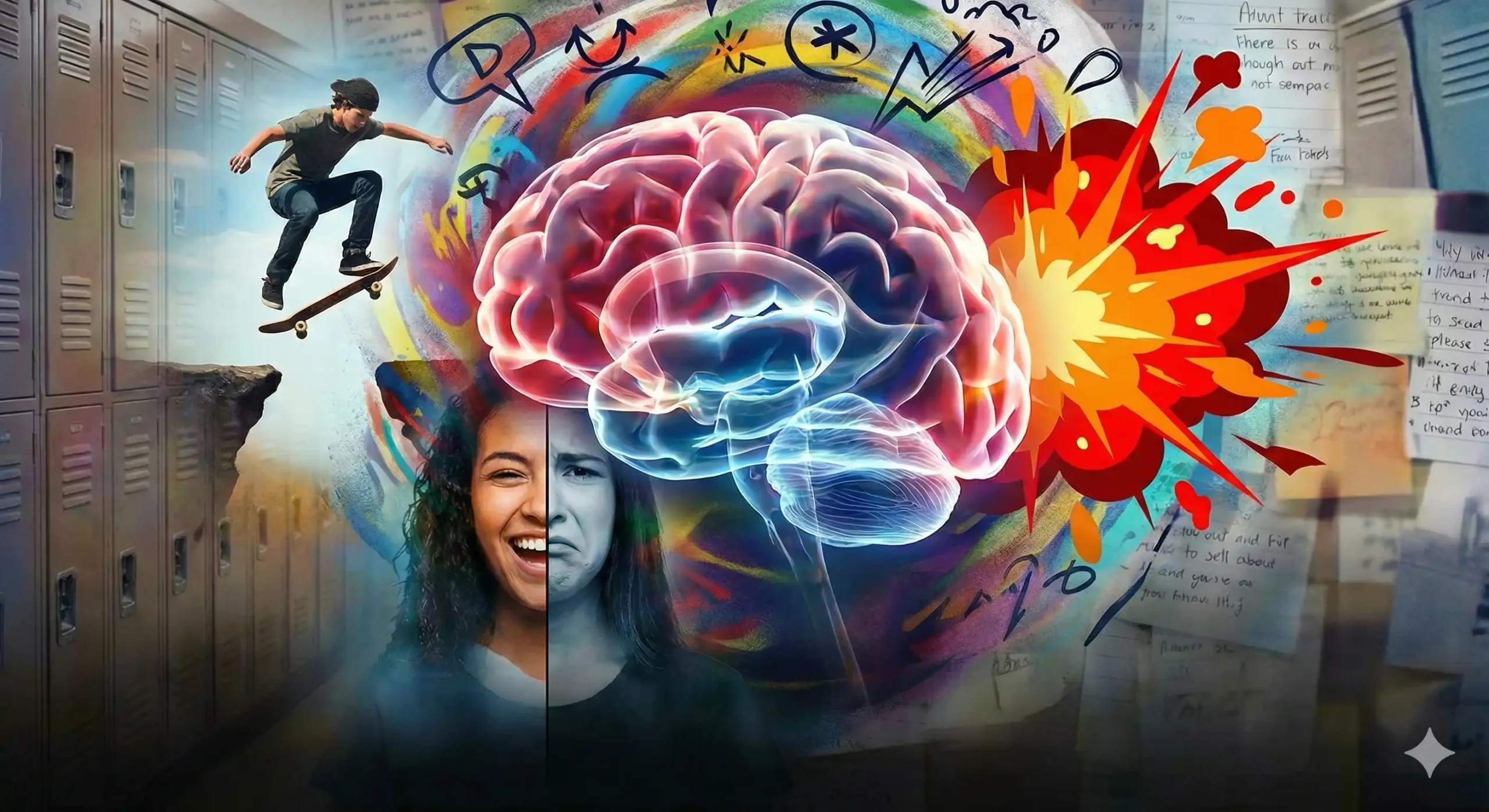

What’s Happening In The Brain?

Eating is one of the most sensory-rich activities we do. Taste, smell, texture, temperature, and even appearance all send signals to the brain at once.

In some children, the sensory parts of the brain are extra sensitive. When certain textures or smells are experienced, the brain misreads them as threatening. This activates the stress response, i.e., the same fight-or-flight system we all have.

When this happens, the brain’s priority isn’t nutrition or learning. Its priority is protection.

That’s why a child might gag, panic, refuse to sit at the table, or melt down, not because they are being difficult, but because their brain feels overwhelmed.

This is more common in children with ADHD, autism, or sensory processing differences, but it can happen in any child.

Is the Eating Difficulty Sensory-Based?

Parents often notice:

- strong gagging or distress with certain foods

- refusal based on texture, smell, or appearance rather than taste

- a very small list of “safe foods”

- anxiety before meals

- emotional reactions that seem bigger than the situation

These responses are real to the child, even if the food seems harmless to us.

Why Pressure Makes Things Worse

A very common instinct is to push harder:

“Just one bite.”

“You won’t leave the table until you eat.”

“They’ll eat when they’re hungry.”

Unfortunately, pressure often increases fear.

A brain in survival mode cannot explore, learn, or adapt. Forced feeding strengthens the association between food and danger. Over time, the list of safe foods may shrink, and anxiety around eating can grow.

This isn’t about discipline or willpower. It’s about regulation.

What Helps Instead: A Brain-Friendly Approach

The first step is safety. Here are strategies that align better with how the brain works:

- Predictability

Let children know what foods will be present. Surprise can increase stress.

2. Exposure without expectation

Food can be on the plate without pressure to eat it. Looking, touching, or smelling counts as progress.

3. Respect safe foods

Safe foods help the nervous system stay calm. Removing them can increase fear.

4. Visual structure

Visual schedules or routine meal patterns help the brain feel prepared.

5. Sensory play outside mealtimes

Cooking, messy play, or food play without eating expectations helps desensitise sensory pathways.

6. Model calm behaviour

Children borrow emotional regulation from adults more than we realise.

7. Seek professional support when needed

Occupational therapists, feeding therapists, or pediatric specialists can guide gradual, respectful progress.

When Should Parents Seek Help?

It’s a good idea to speak to a professional if:

- your child’s diet is extremely limited

- weight, growth, or nutrition is affected

- mealtimes cause significant distress for the family

- eating difficulties are worsening over time

Early, supportive intervention can prevent long-term challenges.

In Sum

When we move from “Why won’t my child eat?” to “What is my child’s nervous system experiencing?” the entire approach changes.

You’re not failing your child. You’re learning how their brain works.

If mealtimes feel overwhelming or confusing, let’s talk. Support, not pressure, helps children eat calmly.